【原文】

Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit: The Song That Remains the Same

This is the story about how Billie Holiday was a true martyr to causes that hadn’t happened yet.

Going on day 12 of protests since George Floyd died in police custody. America is at an inflection point, with tensions reaching an all-time fever pitch. I wince at my own superlatives here, but also at what I know to just be patently true. It’s a demoralizing moment in history when history is not the past. But wait, what? Why? Haven’t we sung this sad song before? Hasn’t Lady Day sung the blues?

The scene: March 1939, New York City. A 23-year-old Billie Holiday has just requested the waiters at Café Society stop serving and for the room to go completely dark. A spotlight casts a sharp beam on her face as she begins her last song of the set, the words suddenly and startlingly searing through a nonplussed audience: “Southern trees bear a strange fruit / Blood on the leaves and blood at the root / Black body swinging in the Southern breeze / Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.”

This elegy for casualties of racism and Holiday’s palpably tragic voice are the ingredients to a perfect storm that changes the atmospheric pressure in the room. No sooner did the spotlight fade than Holiday vanished from the stage. No encore. The song she had just spilled out along with her heart and guts was “Strange Fruit.” Even the radically progressive demographic of Café Society, the wrong place for the right people, weren’t quite equipped to process a reference to the Jim Crow-era lynching terrors. But by the end of the song, it goes over well, really well. Audience members roared with applause and clapped until their hands stung, with a comparably low number of walkouts by obvious racists. But there was no in between.

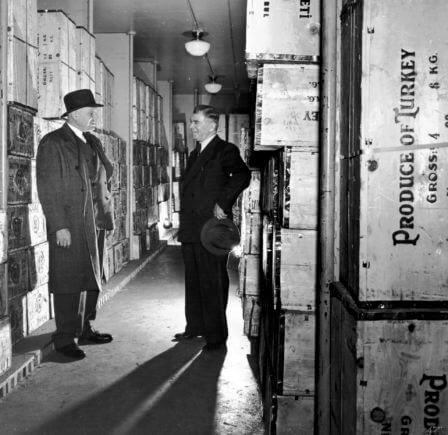

“Strange Fruit” was originally a poem called “Bitter Fruit,” written by Jewish schoolteacher and civil rights activist Abel Meeropol. After seeing an image of the 1930 double lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, a ghastly image which haunted him for days, he was compelled to put pen to paper. Under the alias Lewis Allan he published the poem in 1937 in a union-run teacher magazine.

Meeropol later turned “Bitter Fruit” into a song and introduced it to Café Society owner Barney Josephson, who then asked Holiday to sing it at the nightclub. When she learned the lyrics, she felt both empowered and pained. Though the words moved her, she didn’t particularly enjoy performing the song because it awakened feelings about her father. The manner with which he died deeply disturbed her. Clarence Holiday was denied medical treatment for the color of his skin, and he died at the age of 39. “He had caught a funny kind of pneumonia,” she says in her 1956 autobiography. “I suppose it would be simple now with penicillin and all. But then it was a big deal. He couldn’t eat, couldn’t sit down, couldn’t do anything except walk around town or pace the floor of his room.”

Meeropol was in the audience the night Billie premiered the song. In his description of the right song by the right person performed in the right way, he states:

She gave a startling, most dramatic and effective interpretation, which could jolt an audience right out of its complacency anywhere. This was exactly what I wanted the song to do and why I wrote it. Billie Holiday’s styling of the song was incomparable and fulfilled of the bitterness and shocking quality I had hoped the song would have.

“Strange Fruit,” with its tremendous ovation in a politically liberal community of Greenwich Village, unfortunately would not prove to be a panoptic representation of the nightclub scene comprised mostly of white patrons.

Imagine being raped at the age of 10 by your neighbor, brave enough to come forward, and sent to Catholic School to be silenced and reformed. By the 1920s attitudes of rape weren’t just rooted in patriarchy, they had shifted to downright culpability of the victim. The man, over 30 years her senior, accused Billie of seducing him. Imagine working alongside your mother in a brothel after this experience when other kids your age are practicing The Charleston dance in a Butterick dress. Imagine being that oppressed by poverty and racism.

There was another hellhound on Billie’s trail, hellbound to silence her.

So here was this song, the first real protest in the form of words and music — three minutes and ten seconds when Billie could profoundly decry racism palatable enough for the American public’s consumption. But there was someone determined to put a muzzle on her. Harry Anslinger was the first commissioner of the U.S. Treasury Department’s Federal Bureau of Narcotics during the presidencies of Hoover, Roosevelt, Truman, Eisenhower, and Kennedy and a notorious racist.

After spending 14 years waging a war on alcohol during the prohibition, he was defeated, vengeful, and now looking to eradicate drugs from America forever. Jazz was a personal affront to everything Anslinger stood for. And he grew convinced marijuana was the reason these jazz musicians were intercalating improvised notes, something confusing and cacophonous to him.

The same year Meeropol’s poem was published, Anslinger wrote an article, an appeal to fear called “Marijuana, Assassin of Youth.” He insists the jazzman “does not realize that he is tapping the keys with a furious speed impossible for one in a normal state.”

He wanted not the “good” musicians, but ones of the jazz ilk including Louis Armstrong and Charlie Parker, to be raided and rounded up. He taught his agents that their ace in the hole during a raid of suspected users would be, inexplicably, to shoot first. To be a jazz musician at that time was often an act of self-immolation, many falling hopelessly into the abyss of alcohol and heroin. Kind of convenient for a law-and-order guy who also hates the “black man’s music.”

Anslinger forbid Holiday to play “Strange Fruit.” She refused, so he ordered a witch hunt. Knowing she was a heroin user, he had his agents frame her. They sold her heroin, and she was caught and sent to prison for the next 18 months.

Upon her release in 1948, the federal government refused to renew Holiday’s cabaret performer’s licence, which meant she wasn’t allowed to sing at venues that served alcohol. No longer a member of the nightclub circuit and unable to escape the pain of childhood trauma, Holiday immediately turned to heroin again.

In 1959 she was admitted into a New York hospital with liver cirrhosis and heart and lung problems. Anslinger would stop at nothing. His men entered the hospital room and threatened to arrest her after planting heroin under her bed. They handcuffed her to the bed, took pictures, interrogated her, fingerprinted her, and even removed gifts brought by friends. The agents stationed police officers outside her door and barred any visitors.

The methadone the doctors administered improved Billie’s condition. She gained her weight back and was on the mend. But of course, it was one more thing for Anslinger and his men to declare illegal. The doctors were prohibited to give her further methadone treatment and she died just days later.

One could argue – and oh, I would – the antecedent anthem for the Civil Rights Movement, that signature song of hers, cost Billie her life.

The only surviving filmed record of “Strange Fruit” is from 1959 when she performed on “Chelsea at Nine,” a British cabaret television show. Sadly, she died just a few months later. You can almost read the fight-or-flight on her face as she gulps for additional courage before singing the first verse. Once she does, it’s clear it’s still as primal a need for her as it was exactly 20 years prior. For the two lynched men. For her father. And now for George Floyd, the song remains the same.